In a new series, we ask MobileODT experts to offer their insight on challenges facing the healthcare world. Today, international development specialist and MobileODT Product Manager, Cathy Sebag, shares her view on the biggest challenges facing global women’s health today.

1. Gender-Based Violence (GBV)

Gender- Based Violence (GBV) is a serious challenge to women’s health and well-being. GBV refers to a specific type of violence directed at an individual based on “his or her biological sex, gender identity, or perceived adherence to socially defined norms of masculinity and femininity. GBV can take many forms. “Violence can include female infanticide; child sexual abuse; sex trafficking and forced labor; sexual coercion and abuse; neglect; domestic violence; elder abuse; and harmful traditional practices such as early and forced marriage, “honor” killings, and female genital mutilation/cutting.”

GBV cuts across race, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, age, educational level, and both in developing and developed countries.

Although GBV can impact both men and women, women are particularly at risk.

It’s estimated that one in three women have been beaten, coerced into sex or experienced other abuse. It is not surprising, therefore, that GBV is associated with a variety of consequences including physical and mental health issues that may further limit access to resource health care services, education, and income generating activities.

The health costs of GBV are huge, both the cost of mental and physical health. The World Bank estimates that rape and domestic violence causes 5% of healthy years of life lost to survivors. According to the UN Population Fund, girls aged 15 or younger suffer almost 50% of all sexual assaults worldwide, and LGBT groups face unacceptably high rates of violence.

Violence against women has cost an estimated 3% GDP in some countries.

Reproductive health stands out especially as fear, intimidation, and disempowerment from an intimate partner can prevent the ability to negotiate safe and consensual sex, use and uptake of contraceptive care and planning, and care for vaginal infections or pain.

GBV has a lasting psychological impact. Women who have experienced non-partner sexual violence as twice as likely to experience depression or anxiety. The effects can carry on to the next generation making survivors of sexual violence 16% more likely to have a low-birth-weight baby.

GBV has become a common tool of war. In the current Syrian conflict, women and girls were routinely raped at checkpoints and during interrogations. Even when formal conflict has ended, women and girls can still live with great risk. Widespread GBV can undermine the long-term stability of a society, putting women and girls at a lasting risk. The more violence present in general in a society, the greater risk of GBV posed.

Learn clinicial insights into treating survivors of female genital mutilation >>

Genital mutilation is another pervasive form of gender-based violence. An astounding 200 million women and girls have experienced female genital mutilation, most of whom before their 15th birthday. The extent of the mutilation depends on society and geographical region but has lasting health impacts. In relation to early marriage, girls have a significantly higher risk of unintended pregnancy, pregnancy-related complications, preterm delivery, delivery of low birth weight babies, fetal mortality and violence within marriage.

2. Empowerment within medical care

Empowerment within the healthcare system is still a major challenge for women all around the world. Health systems and services have well-known gender differences- that can ultimately lead to differences in life expectancy, disability, and quality of life. A 2009 policy brief from the World Health Organization, explains that there is increasing evidence that the structure of health systems and even policy may actually make gender inequality worse, failing to address the needs of women, and ensuring they get equitable care they choose themselves.

Women’s experience within the healthcare system can be a significant deterrent to women receiving the best possible care.

For example, many societies around the world remain heavily patriarchal. This impacts healthcare provision as mostly male doctors treat women based on their assumption of women’s needs, rather than including women in the process. There are many countries even require a husband’s signature in order for a woman to receive medical care.

Other studies have shown the significant gender bias in “some medical research areas means that gender differences in the presentation of symptoms, and biological or sex-linked differences affecting correct pharmacological doses, are not fully understood.”

Read how local female physicians are increasing patient trust with patients in Cambodia>>

The complaint that healthcare systems are not structured to empower women’s choices is again an issue that crosses cultural and economic boundaries. In low resource settings, it becomes easier to point to entrenched traditional beliefs and practices as a cause for lacking female inclusion in the medical process. However, studies show that women experience similar limitations even in high resources settings. Studies have shown marked gender differences in the quality of communication between patients and their physicians during the treatment process.

Often, the power balance between men and women lies at the root of women lacking access to healthcare. As the UN Women Watch concluded, “The central issue is male-female power relations, and not merely the lack of health services, medical technology or/and information.”

3. Access to care

A major challenge in women’s healthcare is access to care. Even when women can freely pursue their lives free from violence and have the respect they need to flourish, they may still lack access to healthcare. While not a uniquely female issue, women often suffer the most in medically underserved populations. Communities may lack the necessary access to healthcare because they live geographically far from services. Other times, healthcare centers may not stay open during hours suitable for women to come to the clinic such as when they are engaging in income-generating activities or in charge of child care. Although mobile health clinics and screening camps have made great strides in bringing healthcare to remote and underserved urban areas, there is still much to be done.

Read more about the impact mobile health clinics are having in underserved areas>>

Income equality can also affect access, which means that women may not afford healthcare services or do not have the agency to spend household resources on health expenditures for themselves.

The World Health Organization reports that half the world’s population live without access to healthcare.

800 million people spend 10% or more of their monthly income on health expenses. For almost 100 million people, these expenses can push them into extreme poverty, forcing them to survive on just $1.90 or less a day.

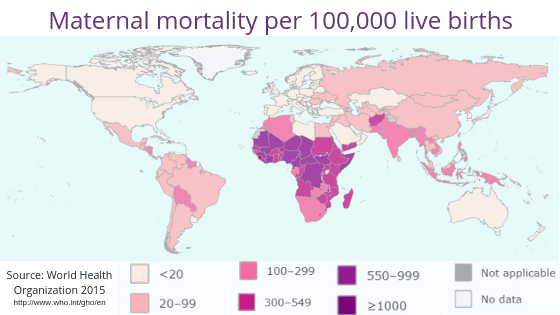

Access to healthcare has significant consequences on women worldwide-whether preventative or symptomatic services. The life expectancy of women born in high resource settings is 24 years higher than women in low resource settings where many women still die in childbirth. As many as 830 women die every day around the world from preventable causes related to pregnancy and childbirth because a lack healthcare can lead to childbirth-related complications. In low resource settings being a mother is a health risk.

The future

There are significant challenges facing women’s healthcare. Still, the future promises improvement as policymakers and providers become more gender sensitive, employing specific strategies to close gaps and promote equality and empowerment. International bodies are putting women’s healthcare on the agenda. Popular movements have brought women’s struggles against sexual violence into the global conversation. While there is a long way to go, I am optimistic that the future holds a better healthcare realty for women, everywhere.

About the author:

Cathy Sebag

Cathy Sebag is an international development specialist with a focus on public-private sector partnerships. Prior to coming to MobileODT, she worked at the US Agency for International Development (USAID,) the Center for Global Development and the UN World Food Program, concentrating on global health and women’s empowerment through program design to improve access, equity, and cost-effectiveness of community-based efforts. She is currently the Product and Marketing Validation Manager, at MobileODT, enhancing strategic engagement with implementers, researchers, partners, and donors.